The 1685 French Code Noir is most often remembered as a brutal assertion of territorial rights, played out in part with horrifying inhumanity towards people of African descent living under French colonial rule. This route considers another group who was affected by the provisions of the Code Noir: Jews, whose only mention was in the first article of the Code, summarily expelling them from French territory. Passing by various sites from the colonial and post-colonial years in New Orleans, when Louisiana Territory changed hands between the French, the Spanish, and the United States, this ride also moves though sites that were important in the early- and mid-twentieth century history of Jewish life in New Orleans.

Turn by turn directions can be found here: https://goo.gl/maps/TgUmDUdcZedCDmCs7

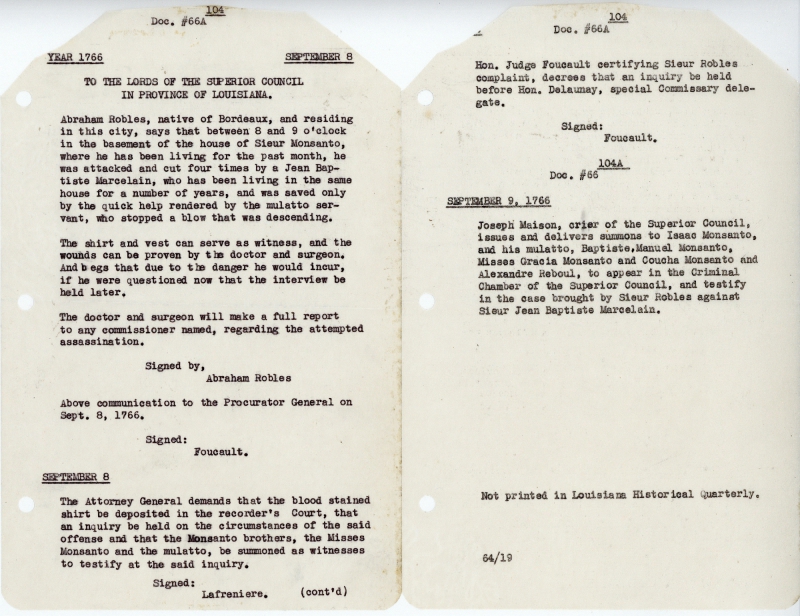

Stop 1: Isaac Monsanto’s house on the 200 block of Chartres Street

As a merchant, Isaac Monsanto traded in various goods, but most pointedly he sold enslaved human beings, building a fortune based in part on human misery. Monsanto and his family lived openly as Jews in the city despite the explicit provision of the 1685 Code Noir prohibiting Jews from living in French territories. In 1768, Monsanto purchased a plantation known as “Trianon” at the site of what is now the Algiers Point Courthouse, where the Monsantos kept enslaved people in bondage to work for their own family. After the Spanish took over Louisiana in 1769, they replaced the Code Noir laws with their own, more rigidly enforced legal rules, and Jews were expelled from Louisiana. Small numbers of Jews managed to stay in the city (sometimes by pretending to convert to Roman Catholicism), and other Jewish families returned with the resumption of French rule in 1800 or, in greater numbers, after the Louisiana Territory was purchased by the United States in 1803.

Isaac Monsanto himself never returned to New Orleans, and instead died in 1778 in Pointe Coupée, where his brother Benjamín had purchased a plantation and was attempting to establish himself as a planter. Benjamín and Angélica Monsanto both moved back to New Orleans, where Angélica owned several properties in the French Quarter, two of them in the 800 block of Chartres. Descendants of Isaac Monsanto also founded the company that became the hugely problematic and predatory multinational chemical corporation that still carries the family last name.

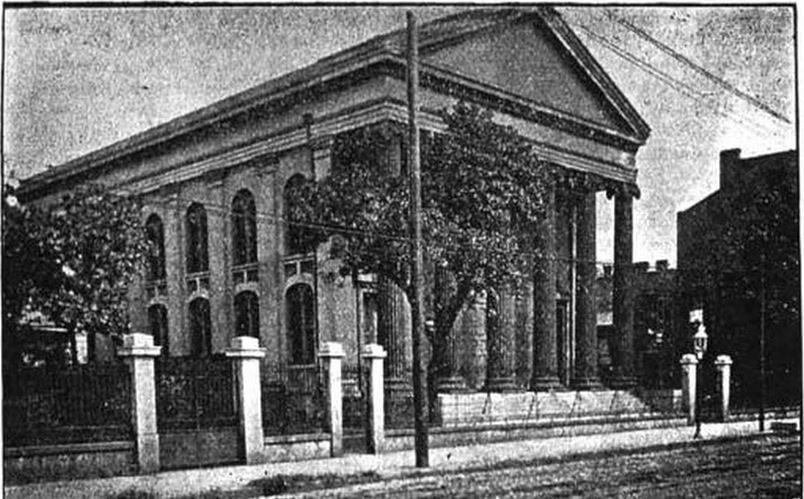

Stop 2: Congregation Shangarai Chasset/Shaarei Chesed (Gates of Mercy)

Stop 3: Congregation Nefutzoth Yehudah (Dispersed of Judah)

In 1881 – in part because of personal and financial stress on the Jewish community and the broader city brought on by the 1878 Yellow Fever epidemic – Shaarei Chesed and Nefutzoth Yehudah merged again to become Touro Synagogue, and in 1908 moved to a new building at Napoleon and St. Charles Avenue (you’ll pass the new building between Lafayette Cemetery and Temple Sinai, stops seven and eight below).

Stop 4: Karnofsky Tailor Shop

The Karnofskys are much more famous, though, for their association with a young boy who worked with Morris and Alex on the refuse wagon, blowing a tin horn to attract customers: Louis Armstrong. Armstrong was born in a house in Jane Alley, but early in his life, he, his mother Mary Ann (or Mayann) Albert, and his sister Lucy moved to the Third Ward near the Karnofskys’ shop. Louis Karnosfky hired Armstrong as a helper (Armstrong later claimed to have been six or seven when he worked with Morris and Alex, and although there are reasons to doubt he was that young it is unquestionable that he was still very much a child at the time). While riding on the wagon, Armstrong saw a cornet in a pawn shop window, but didn’t have the five dollars the store was asking for the instrument. Morris gave him some of the money, Armstrong saved the rest, and that became his first horn. (Some sources claim Morris bought the cornet outright for Armstrong in exchange for a promise that Armstrong would continue working on the wagon for another year). The Karnofsky family also took Armstrong into their home to share meals with him between long shifts on the wagon, and Armstrong heard the family singing Jewish songs, including one that Esther “Tillie” Karnofsky (Morris and Alex’s mother, and Louis Karnofsky’s wife) apparently loved and sang often, “Russian Lullaby.”

In 1913, Armstrong was arrested on New Year’s Day for shooting six blanks from his step-father Tom’s gun, and a judge summarily sent him to the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys for a cruelly open-ended sentence. At the Home, Armstrong took music lessons with teacher Peter Davis, and became a star of the Home’s band. After a year-and-a-half, Armstrong was released from the Home, and continued to play music, eventually landing in Fate Marable’s band and playing on steamboats in the city. In 1922, and at Joseph “King” Oliver’s invitation, Armstrong left New Orleans for Chicago to join Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band.

In Oliver’s band, Armstrong played with the extremely talented pianist Lillian “Lil” Hardin, and the two began a relationship (complicated by the fact that they were both already married but not living with their respective spouses). After obtaining divorces, Armstrong and Hardin married in 1924, and Hardin quickly pushed Armstrong to pursue his musicianship more seriously and to take a leading role with a band of his own. Largely due to Hardin’s encouragement and keen business sense, Armstrong’s career exploded, and he was soon among the most famous musicians in the world. Their marriage, however, did less well, and they separated in 1931 and finally divorced in 1938. (Hardin is worth reading about in her own right too, especially as a pioneering jazz musician who broke gender barriers and won renown for her incredible talent).

Armstrong spent decades touring the United States and the world, becoming arguably one of the most recognizable musicians in history, and unquestionably an absolutely foundational figure in jazz. In 1958, after nearly three decades of national and international fame, Armstrong suffered a massive heart attack following a whirlwind tour through Scandinavia, continental Europe, Israel, Lebanon, and Egypt. From then on, he battled an escalating series of health crises, until his body began to fail and he was hospitalized in New York at Beth Israel under the care of Dr. Gary Zucker. At some point when they were together, Dr. Zucker began to sing a melody that Armstrong knew well: “Russian Lullaby.”

Lying in his hospital bed in 1969, perhaps stirred by the memories of Tillie Karnofsky singing the same melody, Armstrong began a handwritten autobiography that he called “Louis Armstrong + the Jewish Family in New Orleans, La. The Year of 1907.” In the memoir, completed in 1970, Armstrong writes of his fond memories of the Karnofsky family, his love of their music and ritual, and his respect for the ways in which Jews stood together against the systemic oppression and prejudice they faced in New Orleans. Armstrong’s memoir is a strange, deeply contradictory document, at times frankly acknowledging the nightmarish racial terror that Black people faced in the United States, and at other times excoriating them for failing to advance in the way that he saw Jews managing to do. Armstrong is also forthright about the effects of race on musicians’ ability to make a living (suggesting, for instance, that Jelly Roll Morton was able to get more work than other Black musicians due to his light skin), but returns again and again to fond remembrances of the Karnofskys. Despite Armstrong’s experience, there is a history of mutual distrust between Black and Jewish communities that should be frankly acknowledged. Some have suggested that Armstrong may have written the document because of an uptick in Black-Jewish tension in the 1960s (such as the rhetoric of the Nation of Islam). And the memoir often reserves its harshest tone for Armstrong’s father William for abandoning Mary Ann. It’s unclear what his motivations were for writing it, and ultimately the memoir was not published during Armstrong’s lifetime. For a (much) longer examination, read Dalton Anthony Jones’ essay, “Louis Armstrong’s ‘Karnofsky Document’: The Reaffirmation of Social Death and the Afterlife of Emotional Labor.”

Morris Karnofsky (who shortened his last name to Karno for at least part of his life) has another place in jazz history as well. Morris was the proprietor of a record shop called Morris Music Co., located in the early 1930s at 203-205 S Rampart, and then in the late 1930s at 168 S. Rampart (both buildings are long gone). Morris Music was probably the first record shop in the city to sell jazz music, and Morris Karno eventually expanded to sell instruments, including to school band programs. Morris and Armstrong apparently also kept in touch before Morris died in 1944, with Armstrong coming to visit whenever he was in New Orleans. And Armstrong kept a final memento of his relationship with the Karnofsky family and other Jewish friends quite literally close to his heart: for most of his adult life he wore a Star of David necklace, per his words rarely (if ever) taking it off.

2021 Update: the Karnofsky Tailor Shop was once of many building in Louisiana to collapse during Hurricane Ida. Also destroyed was Brandan “BMike” Odum’s Buddy Bolden mural on the neighboring Little Gem Saloon, with only the very top of the mural remaining. However, the “The Model Tailor” tiles are still visible on the ground in front of where the building once stood.

Stop 5: O.C. Haley/Dryades Street Commercial District

In the 1980s, New Orleans renamed a section of Dryades for Oretha Castle Haley, a Civil Rights organizer and a president of the New Orleans chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). As a college student, Haley joined the 1960 boycott of businesses on Dryades Street that wouldn’t hire Black sales clerks or cashiers, despite the fact that the majority of customers in the area were Black.

Some stores chose to desegregate their work forces and hire Black New Orleanians at all levels. Others, however, chose to close and move to the much whiter suburbs.

Stop 6: Congregation Shaarei Tefiloh (Gates of Prayer)

In 1975, Shaarei Tefiloh moved to a new building in Metairie, where the congregation is still based. The building on Jackson Avenue fell into disrepair and was eventually purchased in 2012 and converted into condos. Although it is no longer a synagogue the Jackson Avenue shul is still one of the oldest existing synagogue buildings in the United States.

Stop 7: Lafayette Cemetery No. 1

Or you can listen to Emily herself in this video!

(Unfortunately, Lafayette No. 1 is currently closed for maintenance, and will not re-open soon. However, you will be able to see into the cemetery from the Washington, Prytania, Coliseum, or Sixth-Street gates, but won’t be able to go in. Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 is located on Washington as well, about ten blocks towards the lake from Lafayette No. 1. There are likely no gravestones cut by either Lowenstein or Kursheedt at Lafayette No. 2, even though the cemeteries are fairly similar in age. However, there are interesting labor history connections with Lafayette No. 2, including to Benevolent Societies found by Black New Orleanians).

Stop 8: Temple Sinai

Stop 9: Butterfly Riverview Park (the Fly)

It is our city, built of our silences and strengths, that is in the balance, here today.

In the shadows of shortening days, on the bright edge of the New Year,

We come bearing the heft, the inevitable weight of a full year’s

Decisions and inactions, movements and hesitations.

We come to fill our hands with what we have not done

And what we have. To empty them, to free them for work.

To empty them until there is nothing left but the space of a doorway that we can step into, together

With a New Year’s commitment to the balance of our city.

While you are riding, bring masks and hand sanitizer, respect physical distancing, and make sure that you have an emergency contact who knows where you are and can pick you up if needed. We also have some more in-depth tips for safe biking in the pandemic, check them out! Please be aware that NOLA to Angola cannot provide logistical or emergency support to individual riders this year. Take care, and safe riding!