Gentilly & New Orleans East

Stop A: the Flooded House Museum

Stop B: the former St. Bernard housing projects

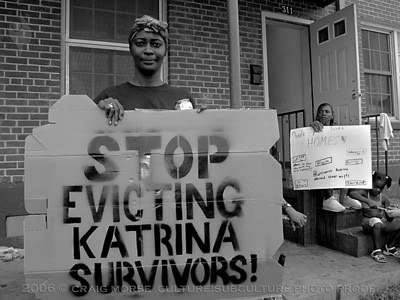

The forced evacuation caused by Katrina coincided with a desire on the part of government agencies and local business interests to replace the projects with more profitable development. Just days after the storm, Congressman Richard Baker of Baton Rouge said “We finally cleaned up public housing in New Orleans. We couldn’t do it. But God did.” Finis Shellnutt, a New Orleans real estate developer rejoiced, saying, “The storm destroyed a great deal and made plenty of room to build houses to sell for a lot of money. Most importantly, the hurricane drove poor people and criminals out of the city, and we hope they don’t come back.”

Although the buildings themselves were minimally damaged, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) boarded up almost all of the projects right after the storm, enclosing them behind locked chain-link fences and forbidding access to residents. People were not even allowed inside to retrieve their belongings.

As demolition plans began to take shape, residents and their supporters protested. St. Bernard residents were determined and persistent, camping in a tent city outside their fenced-off homes. But their pleas were ignored: the agenda had been set before the storm ever reached the city.

The decision to destroy public housing was made official at a shocking City Council hearing where councilmembers voted unanimously to demolish all 4,500 units of the “Big Four” public-housing complexes: St. Bernard, B.W. Cooper, Lafitte, and C.J. Peete. Hundreds of people showed up at City Hall hoping to testify, but many were locked out, their protests met with pepper spray and tasers. Former Mayor Ray Nagin said the City Council’s decision was one of “compassion, courage and commitment to this city,” calling it an “incredible day.”

Before Katrina, the 2000 Census recorded 2,020 occupied units in the St. Bernard projects. Columbia Parc, the complex now that stands in the St. Bernard’s footprint, allocates only 157 of its 500 units to residents eligible for public housing.

Where did the thousands of St. Bernard residents whose public housing units were not replaced wind up? Keep biking to learn more.

Stop C: HANO/Housing Vouchers

These vouchers were intended to allow former public-housing residents spread out into neighborhoods with less crime, less poverty, and better educational and job opportunities. But according to a study by the Fair Housing Action Center, 42 percent of voucher holders have wound up packed into just 13 percent of New Orleans’ Census tracts. Overwhelmingly, these neighborhoods are “low opportunity,” marked by inadequate transit, health hazards and a lack of basic services.

The majority of these neighborhoods are in New Orleans East. A lack of investment after Katrina created these conditions- only one grocery store reopened in the immediate aftermath of the storm, and the area had no hospital until 2014. The bus lines that serviced the East before Katrina have been cut, and their frequency reduced.

Once a neighborhood becomes “low opportunity” a sort of feedback loop develops. The lack of opportunity makes it difficult to attract residents. A lack of residents translates to a lack of support for improving infrastructure. And without infrastructure, a neighborhood is less likely to secure the type of investment that creates opportunity for residents.

Stop D: ‘The Yellow House’

In 1961 the home at 4121 Wilson was purchased by Broom’s mother. A 19-year-old widow, she purchased the house with her late husband’s life insurance. She is the first person in her family to own a home. She is also a pioneer in New Orleans East- large-scale development of the area began in 1959, and was spurred by employees seeking homes convenient to the many good jobs at the NASA facility in Michoud and other industrial employers like Folgers Coffee. Developers promised New Orleans East was a place were you could live the suburban dream: a middle-class standard of living with rising home values.

In the 1960s Broom’s mother remarries to a widower. Both have children from their first marriages; they go on to have 6 more kids together. Their house is one of 5 on the block. Other families on the street also have young children and this small neighborhood becomes their playground. A trailer park across the street houses employees who have come from out of state to work at NASA in Michoud. At the time this facility is one of the largest assembly plants in the world, housing not only NASA but also Boeing, and Chrysler. Broom’s father works there, as do members of Broom’s extended family.

Here are Broom’s words on the 1970s in New Orleans East (instead of your author’s 7th grade book report level stylings):

Big changes, the ones that reset the compass of a place, never appear so at the outset. Only time lets you see the accumulation of things. Nothing about the dream of New Orleans East Inc. had come to pass. The area contained 8,000 residents in 1971; 242,000 fewer than its original goal.

…In 1972, the Apollo missions ended, reconfiguring things at NASA’s Michoud plant, which had, most notably, built the first-stage Saturn V rocket that launched astronauts to the moon. Though the plant added $25 million to the local economy and (Broom’s father) kept his job, the 12,000 employees, counted in 1965, dwindled to 2,500.

…Residents in Pines Village, one of the earliest eastern neighborhoods, minutes from (4121 Wilson), were threatening lawsuits against the city’s Sewerage and Water Board for “mental anguish and anxiety suffered during floods and all heavy rainstorms.” The city, they claimed, approved developers’ plans even though they knew elevation was too low for sufficient drainage, a problem exacerbated by new communities that further taxed the substandard drainage systems, “negligence … that is injurious to our health and safety,” one prophetic-seeming letter writer said…“This area to the east is not a mirage. It will not go away if you ignore it. It will stay and haunt you if you do not start thinking of it as a part of the city.”

By the late 1970s, the racial composition of the East had flipped. Within twenty years, the area had gone from mostly empty to mostly white (investment) to mostly black (divestment).

Broom is born in 1979 and her father passes away just six months later from a brain aneurysm. The divestment in New Orleans East continues into the 1980s:

New Orleans East was no longer majority white as it had been a decade before. Everything in the East slipped—into stasis, entropy, full-blown disrepair. The oil bust in the late 1980s led to a surplus of empty apartment buildings meant for employees who would work for booming industries that never materialized. Those became subsidized housing for poor black people pushed from the city’s center, where real estate was more valuable, to its “eastern frontier.”

When Broom is a teenager in the mid 1990s, the aftermath of the collapse of New Orleans’ oil business in the 1980s is acutely felt and experienced in the East. Of 1994, she writes:

There was no work in New Orleans East now. The Plaza mall…was on its way to dead, having once been a vast labyrinth (eighty acres, one hundred plus stores). When it opened in 1973, a mariachi band played in front of Fiesta Plaza Ice Rink.

…But now there were Night Out Against Crime meetings in the mall’s parking lot. Going there put you at risk of being held up (before you could step foot out of the car) by a person with a gun…the customers, now mostly high school and middle school students, stole their wares.

The short end of [this] street ate whole members of its own body….[residents would move out and their homes would be razed the next day]. Structures could disappear overnight and without warning, carried off during our sleep. The land that had been Oak Haven trailer park was now bare, its out-of-the way status perfect for illegal dumping executed by people who were bold enough to do it in daytime. Eventually, it became an official business, junk cars lifted between steel maws and crushed, stacked high like game chips. The junk was winning. The short end of Wilson had become more industrial than residential.

Broom leaves Louisiana for college and works at a coffeehouse in the French Quarter in the summers. This is the first time she has spent extensive time in the Quarter, and becomes aware of the many distances between it and her home here on Wilson.

Nothing in the landscape of New Orleans East signaled the New Orleans of most people’s imaginations. No iconic streetlamps lighting blocks of brightly painted shotgun houses. No street musicians playing in the flat industrial landscape that contains very little arresting detail, being littered with motels, RV camps, and auto shops. No streetcars running, no joggers alongside them. Walkers here did not stroll. They walked out of necessity. There were few restaurants, no cafés to pass by or stop in. But none of those details made New Orleans East any less of a place.

For the me of then, the City of New Orleans consisted of the French Quarter as its nucleus and then all else. It was clear that the French Quarter and its surrounds was the epicenter. In a city that care supposedly forgot, it was one of the spots where care had been taken, where the money was spent. Those tourists passing through were the people and the stories deemed to matter. Those of us who worked in the service industry all converged on this one place, parts of the machinery that maintained the city’s facade, which did not seem like a ruse to me then.

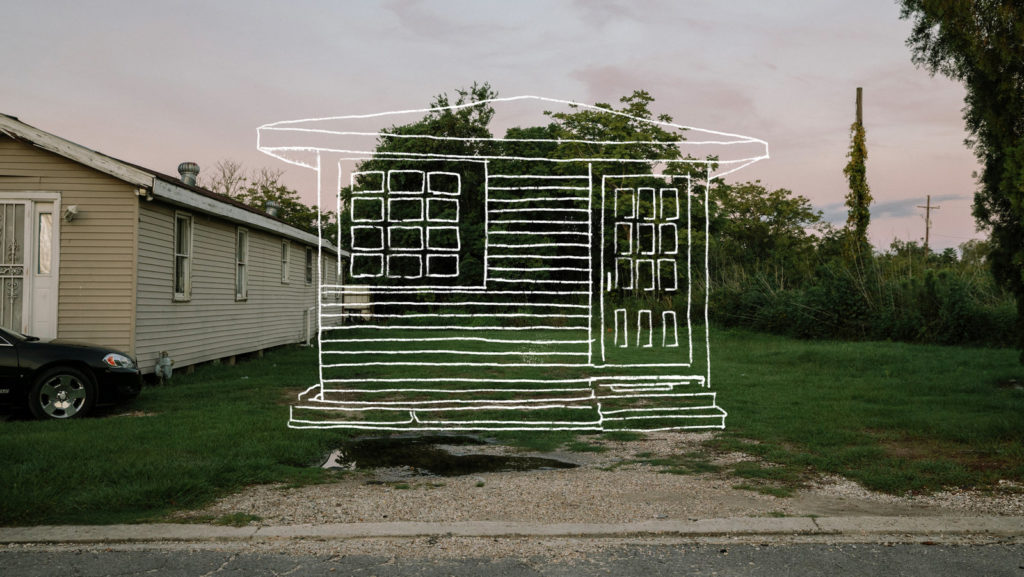

In 2005, Broom is living in New York. Her mother has moved out of the city; the house at 4121 Wilson remains in their family as a residence for anyone who needs it, and is cared for by Broom’s older brothers. The levee failures after Katrina fill this neighborhood with over 10 feet of water; when the flood recedes, 4121 is extensively damaged: “The house looked as though a force, furious and mighty, crouching underneath, had lifted it from its foundation and thrown it slightly left…we poked our heads through blown-out windows— peered into the living room through the wide-open frames. Walked along the side and stood in front of the new entrance, a fourth door designed by Water.”

In 2006, the house at this address was demolished by the city before anyone in the Broom family could protest or intervene. In a classic instance of the cruel & absurd incompetence that ruled life after Katrina, the demolition occurred after a single notification was mailed to the empty home.

Stop E: The Grand Theatre

“Spaces like this are disconnected because they’re eyesores,” said Odums of the mural. “I’m interested in how art and paint can be used to reconnect a community…now that this space has become a focal point and people have positive memories, whether it was from the Grand itself or whether it’s from the painting, (I hope) that they could insert that positive intention in to what it could be,” he said.

The building (along with the mural) was demolished after a fire in 2019.

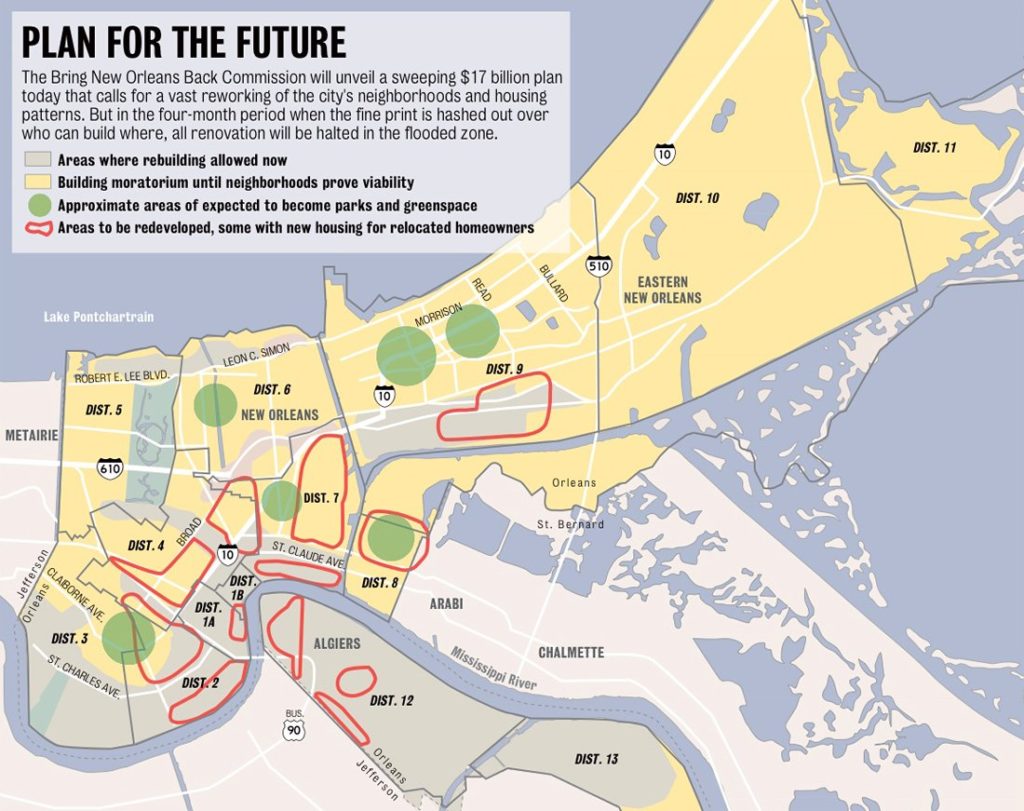

Stop F: Welcome to a Green Dot

After a furious response from residents whose neighborhoods had been slated for demolition, the plan was eventually scrapped. However, the damage was done in the form of perceived uncertainty by the government about the viability of ‘Green Dot’ neighborhoods.

“It left the perception that New Orleans East would be closed for development,” New Orleans East homeowner and civic leader Ron Wright says. “That really discouraged a lot of people who were trying to decide whether to come back and created a huge risk for those who did.”

Stop G: Discrimination and the Road Home Program

Homes in New Orleans’ historically black neighborhoods generally had their values depressed due to decades of racial discrimination that caused and reinforced segregation in housing.

Two of the lead plaintiffs in a class action lawsuit against the Road Home program and its discriminatory practices are homeowners in this neighborhood. Their home was valued at just $135,000, although their rebuilding costs were estimated by the state to be $308,000. They received a Road Home grant of $16,649 to supplement just over $100,000 they received in insurance payments, leaving them $190,000 short of the funds they needed to rebuild and return.

They were forced to move back to their home before it had electricity and hot water because they couldn’t afford renting an apartment and paying the mortgage. They were able to make piecemeal repairs to their home over the years (one of the homeowners described the process as “[I] might buy enough sheetrock for a room, then wait another month to buy some more”). Major expenses like kitchen cabinets and counters, repair to structural damage from falling trees and a new roof were still out of their reach in 2011.

During the years that the state fought the Road Home discrimination lawsuit, one half of the couple dropped out of college a few credits short of a degree in accounting in order to return to work and save money for home repairs. The other had a heart attack. Their bank attempted to foreclose on the home twice.

In 2011 a federal court found that the Road Home program had no legitimate reason to base grants on home values rather than repair costs. Despite this victory on paper, the homeowners described above did not receive any funds from the lawsuit’s $62 million settlement. The reason why? By moving back into their home, they became ineligible for rebuilding assistance.

Stop H: Lincoln Beach

In the 50s the city doubled down on the ‘separate’ side of ‘separate but equal’ and upgraded Lincoln Beach. White sand, swimming pools, a bathhouse restaurant, and rides and attractions were all added. New Orleanians of this era recall a long, hot and dusty ride out to the site. And what awaited beyond the gates was wonderful.

Irma Phillips of New Orleans recalls: “My family and I, we were able to go to Lincoln Beach and shed ourselves of racism. Lincoln Beach was a shelter of calm, peace, and laughter for us…and we didn’t have to worry about people throwing rocks at us, calling us filthy names. It was just peaceful.”

In addition to this peace was the celebration of black music and culture. Lincoln Beach hosted beauty contests, diving competitions, even a black state fair. At night musicians such as Fats Domino, Little Richard, the Neville Brothers, and Irma Thomas took the stage.

After the 1964 Civil Rights Act integrated public spaces by law, Lincoln Beach became, for the city, useless and expendable. All funding for the site was revoked and it closed soon afterward.

By the early 1990s, residents and community groups launched a campaign for “equity in the development of the lakefront” that centered on the unfulfilled promise of Lincoln Beach. The renewed redevelopment efforts culminated in a 2004 plan, in which artist John Scott was commissioned to create a spectacular piece of public art that would celebrate the site’s history.

Scott was a New Orleans native who visited Lincoln Beach in its heyday. His vision for the site was a “visual polyrhythmic environment,” with custom gates similar to the ones he constructed for the New Orleans Museum of Art, bronze shelters with “shadow sculptures” of musicians and restoration of the original sand beach. The centerpiece was to have been a series of floating sculptures he calls an “aquatic second line.”

5-foot metal figures of musicians and dancers will be cut in various colors of anodized aluminum, the same material used to create Mardi Gras doubloons. They will then be mounted on 34 buoys around the perimeter of the beach’s designated swimming area in Lake Pontchartrain to “dance” with the wind and wave action, resembling the real-life celebratory processions.

While funding was secured for Scott’s project, construction issues in the summer of 2005 stalled its progress and Katrina’s landfall destroyed any possibility that it would ever be built.

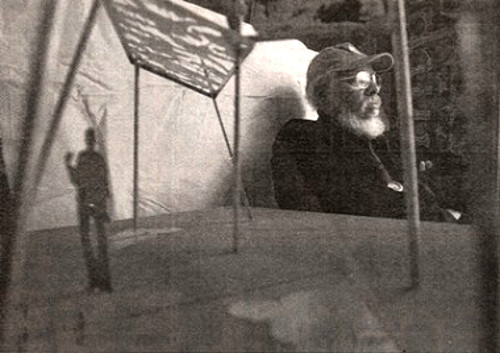

Sculptor John Scott with a model of a Lincoln Beach “shadow sculpture”. Photo from the Times-Picayune

Sculptor John Scott with a model of a Lincoln Beach “shadow sculpture”. Photo from the Times-PicayuneIn the wake of Katrina’s destruction, restoring Lincoln Beach became an afterthought. This past summer, a transformation began to take place.Community members initiated their own revitalization efforts, organizing cleanups of Lincoln Beach and removing 250 contractor-size garbage bags of trash from the site.

They are now campaigning to reopen the site in a way that doesn’t commercialize or gentrify Lincoln Beach and push out the people for whom it was originally built. You can support their cleanup and advocacy efforts via their Facebook Group, New Orleans for Lincoln Beach.

Stop I: Jazzland

Plans to redevelop the site have come and gone. For a while, it was going to be an amusement park again. Then it was going to be an outlet mall, until the Riverwalk downtown decided it wanted to be an outlet mall. It has occasionally been rented out for filming; the action movie about the ‘Deepwater Horizon’ disaster was filmed in its parking lot, where a 70 foot tall replica expoding oil rig was built on site. The most recent plan (a green conference center/zipline course) is likely to become a casualty of COVID-19.

As it stands it is a monument to neglect. Every person who passes by has little choice but to gasp at the enormity and longevity of its ruin. Some get a hit of post-traumatic stress from Katrina at the sight of it. Has it been left like this because of a hope that the grand scale of its decay might prompt an equally epic redevelopment, or the fear that once it’s gone it and the need for investment in New Orleans East will become invisible?

Finally, one final question for y’all to contemplate on the ride back into town: what can the community do to reclaim this place?

Recommended Reading:

Nora Goddard, ‘The Destruction of Public Housing in New Orleans’

Sarah Broom, The Yellow House. Grove Press, 2019

Andy Horowitz, Katrina: A History, 1915-2015. Harvard University Press, 2020

Andrew Kahrl, ‘The Making, Unmaking and Memory of Black and White Beaches in New Orleans’

James Cullen, ‘Keeping the Peace at Lincoln Beach’

Downtown & the Lower 9th Ward

Turn by turn directions can be found here: https://goo.gl/maps/9aPduvXi55Dkm4ceA

Stop A: Charity Hospital

The hospital weathered the hurricane without significant incident, but the levee breaches caused the basement and part of the first floor to flood. Because much of the facility’s mechanical infrastructure was located in the basement, the hospital lost electricity and running water. Patient and staff evacuation was completed 5 days after Katrina’s landfall.

After evacuating, Charity staff expected that they would be back in the building treating patients within a matter of weeks. After the floodwaters receded, doctors, nurses, military personnel, and civil engineers worked together to clean up the building. But once the first three floors were scrubbed and the doctors pronounced them ready for use, all medical personnel were ordered out of the building and warned not to return. Hospital security intimated that if they did return, they would be charged with criminal trespassing.

LSU’s Health Care Services Division (which operated Charity) had made plans to replace Charity years before Katrina. The hurricane and flood became LSU’s excuse to build a sprawling, expensive new facility with government support. Blocking Charity’s reopening by claiming that it was too damaged and unsafe was crucial to securing a windfall in federal funding.

Former State Treasurer/current Senator John Kennedy says that after the storm, as Charity sat idle, he asked LSU hospital CEO Don Smithburg, “Why not move back in at least temporarily?” Smithburg’s response? “If we do, we will never get a new one.”

Federal disaster policy created a financial incentive to keep Charity closed. When the cost of repairing a damaged public building to its predisaster condition was less than 50 percent of the cost of replacing it, FEMA would pay for the repair. But when the cost of repairs exceeded 50 percent of the replacement cost, FEMA would pay for a full replacement.

State officials, including Governor Kathleen Blanco, backed LSU’s refusal to repair and reopen Charity. Blanco declined federal funds to get the hospital up and running, but fast-tracked repairs on the Superdome to get it ready for the 2006 football season. The payout LSU was hoping for did not arrive until 2011, and the new University Medical Center did not reopen until 2015.

In the meantime, Charity’s closure destroyed New Orleans’ safety net. Patients who had relied on one of Charity’s 160 prestorm primary care clinics had their access to preventative care disappear.

Charity had 128 long-term inpatient psychiatric beds and fifty crisis intervention beds, which also vanished overnight. The largest inpatient care center in the city became Orleans Parish Prison.

LSU’s refusal to reopen Charity undoubtedly cost many New Orleanians their lives. Dr. Kiersta Kurtz-Burke, a formet Charity physician, said that “They didn’t die on a rooftop, they didn’t die in an attic, they didn’t die from drowning, but these are people who are really victims of disaster—and of the response to the disaster, of choices that were made in the rebuilding of the city.”

Stop B: The Streetcar to Nowhere

This expanded streetcar line has been a boon for economic development and tourism and accelerated displacement due to rising housing costs. It doesn’t serve areas where public transit has been cut (the route was well-served by bus lines beforehand). It has also diverted funds from bus service.

Before Katrina, there were 19 high-frequency bus and streetcar lines that served the city. Now only 5 routes run at that frequency that can be considered truly useful and convenient (every 15 minutes or less). 2 of these 5 routes are streetcar lines. If you have the time, wait at this bus stop and see what shows up first: an empty streetcar on the Rampart line or the Elysian Fields bus.

Stop C: Industrial Canal breach site

In the aftermath of Katrina, the failure of this levee and the destruction that followed in this neighborhood was often spoken of as if it were a foregone conclusion, with the flooding that occurred in 1965 during Hurricane Betsy cited as proof that it had been doomed for years.

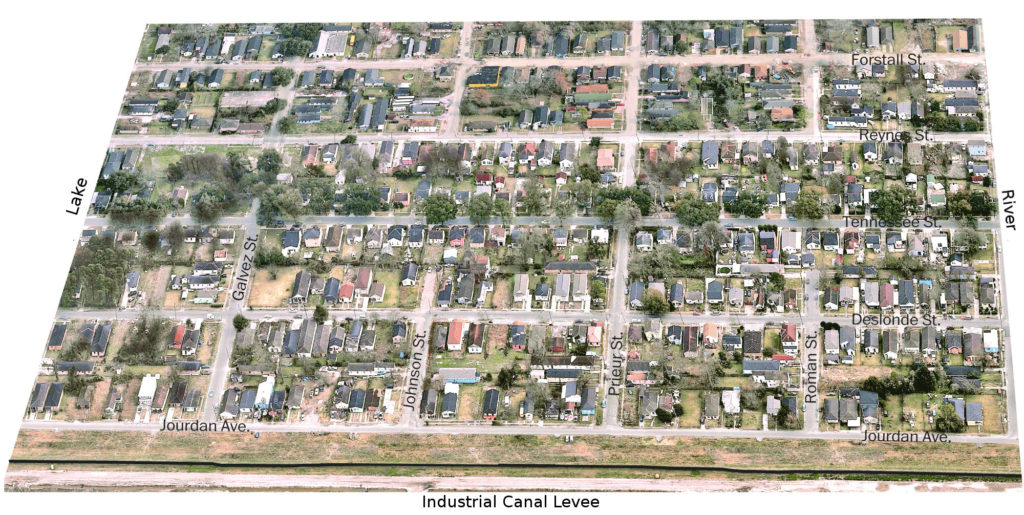

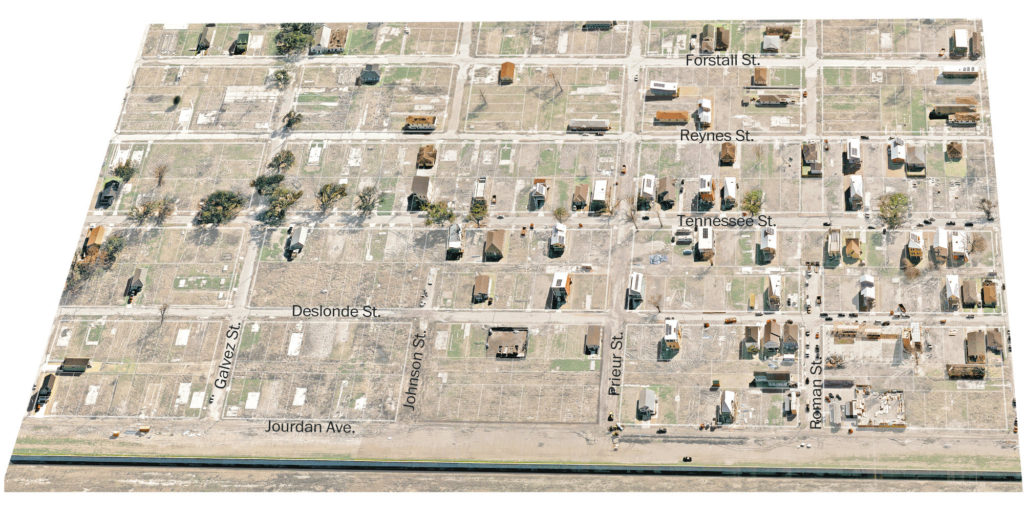

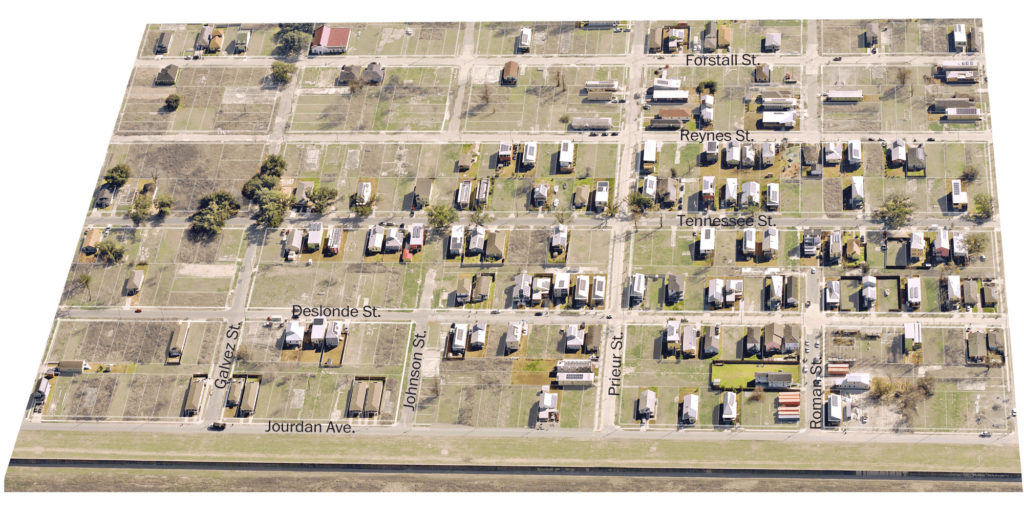

In both cases, the extensive flooding in the Lower 9th can be attributed to the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO). It funneled storm surge from Betsy to the Industrial Canal, overtopping this levee. The same intensification of storm surge from the MRGO took place during Katrina, and was compounded by 40 years of environmental destruction. There will be more on MRGO later in the ride. For now, please click through the images below to see an overview of this site in 2004, 2005, 2008, 2010 and 2015.

Stop D: The Lower Ninth Ward Living Museum

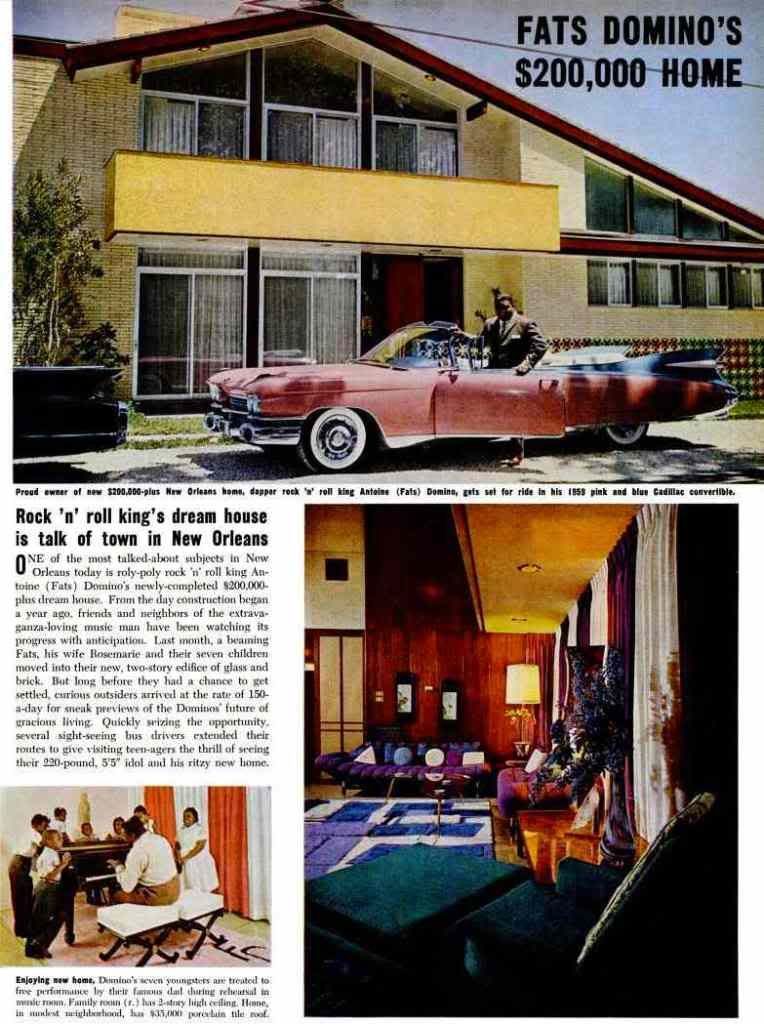

Stop E: Fats Domino’s House

When Domino was born in 1928, the area above Claiborne Avenue lacked electricity, indoor plumbing and paved streets. Many residents harvested cypress trees from the swamp at the back of the neighborhood, using the wood to build their own homes. His neighbors raised farm animals, and his mother grew vegetables to feed her children. His family had moved to the city from Vacherie, where his father had worked on a sugarcane plantation. His parents settled in the 2400 block of Jourdan Avenue; Domino’s uncle and eldest brother also built homes on the same block.

By 1960 the area was full of modest, single-family houses. Domino bought up a few lots and built a modern split-level home with 24-foot ceilings. He wasn’t there to show up his neighbors, though- he was giving them a place to hang out and drink beer while he cooked red beans for everybody.

In 2005, as Katrina approached Domino and his extended family gathered in this home to ride out the storm. When the Industrial Canal’s levee failed, floodwaters quickly filled the house’s first floor, but the structure held. Days later, rumors led someone to spray paint “R.I.P. Fats You will be missed” on the balcony. As it happened the reports of his death were greatly exaggerated- the Dominos had been rescued, and had managed to get to Baton Rouge.

After resettling in Harvey, Domino couldn’t wait to move back to the place he had always called home. “I ain’t too far from my neighborhood. Fourteen, fifteen minutes,” he said in 2006. “I’m going to wait it out. I’ll be there pretty soon, I hope. I don’t think I’ll leave the Ninth Ward.”

While his house was restored, the neighborhood he once called home had disappeared. Most of his old neighbors had left, died or never returned. Domino never returned to live in the Ninth Ward permanently, staying on the Westbank until his death in 2017.

Stop F: Burnell’s Market

The CVS at 5000 North Claiborne also opened in 2016. Its construction was subsidized by tax breaks from New Orleans’ Industrial Development Board. It closed 4 years later during the first financial quarter of 2020, when CVS posted over $2 billion in profits.

Burnell regularly works 17-hour days in his market, and is likely to be on site. If you go inside, MASK UP!

Stop G: Successions

“This was one of the first subdivisions that was designated for African Americans. The idea was just so wonderful to be able to buy a lot for $250, to build a house and be a homeowner. When my family first came here, we cut a street, a path really, to get back to this lot. In the Ninth Ward, you’ve got a group of people who have stayed because we wanted to – because we’ve got an investment in this community.”A 75-year-old lifelong resident, speaking in 2003

The deep roots families have in this neighborhood created an unexpected barrier to recovery after Katrina. Homes were often passed down through generations by inheritance laws or by family agreement without transferring title to the property via a succession (a/k/a ‘probate’ outside of Louisiana). Recovery policies privileged individual ownership of homes and didn’t take into account the practice of family determining ownership of a deceased relative’s home outside of court. Insurance companies and government recovery agencies required clear title to a home before they’d provide the funds needed to rebuild.

Owing to the common practice of not filing successions, the name listed on a home’s title would often be that of its long-deceased original property owner. In order to clear the title, the current homeowners had to complete complex and costly legal procedures to formalize their ownership rights. One process required the signed consent of all eligible heirs- diagramming and documenting the relevant family details of death, birth, marriage, and divorce in order to determine other possible heirs to the property, then tracking everyone down and securing their power of attorney.

In the Ninth Ward, a lack of clear title stood in the way of 1300 Road Home applications that were delayed or rejected as residents tried to demonstrate ownership of their homes. Some have not been able to prove ownership even now, 15 years after Katrina.

While the issues created by a lack of clear title directly impacted individual families, their effects also radiated outwards to neighborhood blocks and beyond. Resolving title and ownership slowed down recovery efforts and translated into high levels of blight and vacancy, further increasing social inequality in post-Katrina New Orleans.

Stop H: Bayou Bienvenue

The residential portion of the Lower 9th Ward that you just rode through was built on the edge of this wetland. What remained at the back of the neighborhood was an old–growth swamp filled with cypress and water tupelo trees, water lilies, and freshwater wildlife such as fish, alligators, otters, birds, and crawfish.

This swamp provided neighborhood residents with fish, game, wood and recreation. It also served as a “horizontal levee” of sorts- cypress swamps absorb the height and speed of a hurricane’s storm surge and shelter man-made levees from waves.

As man-made environmental change occurred in the area the wetlands in this area were slowly destroyed. The Industrial Canal was the first cut, creating a path through this delicate freshwater ecosystem to brackish Lake Pontchartrain. Rapid destruction began in 1957, when construction of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) began.

The MRGO was a shipping channel that connected the Gulf of Mexico to the Industrial Canal. It carried salt water from the Gulf into this area and other cypress swamps in its path, destroying tens of thousands of acres of wetlands that protected the city from storms.

The loss of these natural buffers funneled Katrina’s storm surge up the length of MRGO and into the Industrial Canal, leading to catastrophic flooding in New Orleans East, St. Bernard Parish, and the Ninth Ward. Research has shown that this neighborhood would have experienced 80% less flooding if saltwater from the MRGO had not destroyed so much nearby swamp.

The destruction of this small ecosystem mirrors what is happening on a larger scale elsewhere. Oil & gas interests have cut canals through Louisiana’s coastal wetlands, allowing saltwater from the Gulf to destroy massive amounts of protective wetlands along our southern shore. Rising sea levels are accelerating the loss of wetlands on coastlines everywhere.

The neighborhood you’ve biked through today shows us the cost of wetland destruction. What has happened in the Lower 9th is just a preview of what hurricanes could do everywhere in the future. And when that future arrives, what kind of example has the Lower 9th after Katrina given us for rebuilding?

Stop I: Sankofa Wetland Park (& optional bonus level)

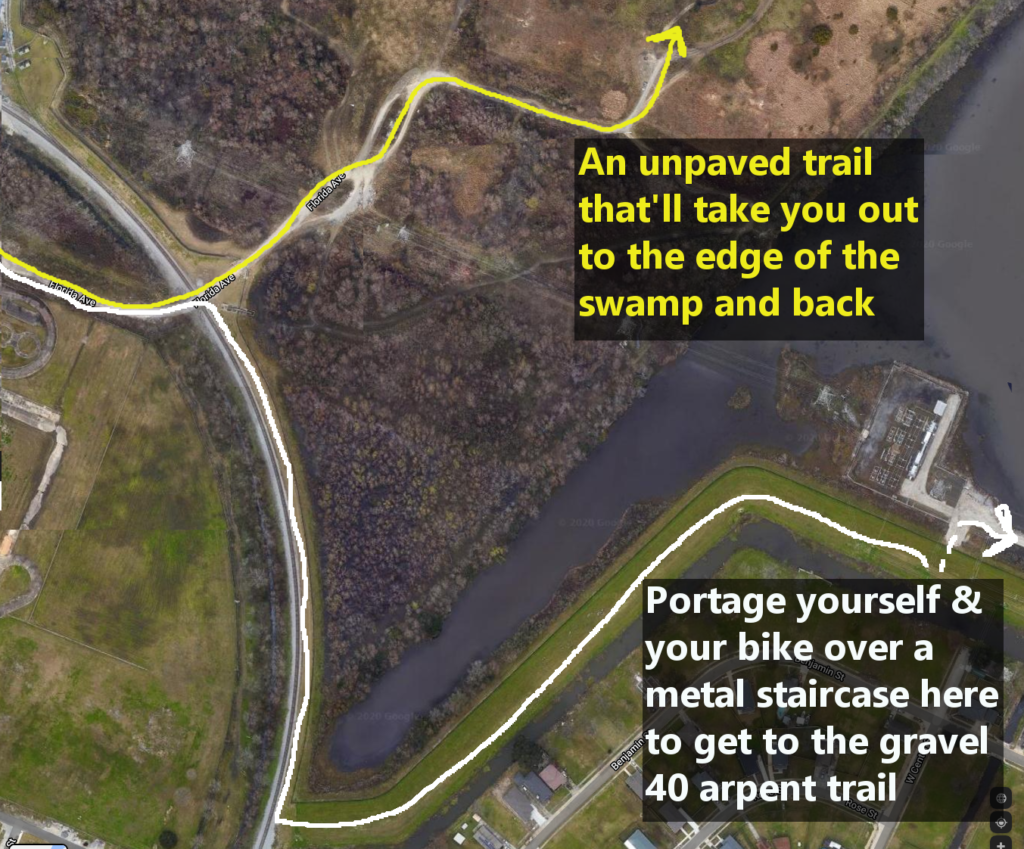

If you’re in the mood for even MORE swamp and MORE miles, you can continue on Florida Avenue up the levee and past the railroad tracks. You can then continue straight onto an unpaved loop through a former landfill (this is nicer than it sounds), or turn right and ride on the levee over the parish line to the secret back way to Chalmette’s gravel 40 Arpent Canal trail. (See the map below.)

Recommended Reading/Viewing:

Kenneth Ott, The Closure of Charity Hospital After Hurricane Katrina: A Case of Disaster Capitalism. Master’s thesis, University of New Orleans

Ride New Orleans, ‘The State of Transit 2019’

Richard Kluckow, The Impact of Heir Property on Post-Katrina Housing Recovery in New Orleans. Master’s thesis, Colorado State University

Restore the Bayou, ‘Bayou Bienvenue’

While you are riding, bring masks and hand sanitizer, respect physical distancing, and make sure that you have an emergency contact who knows where you are and can pick you up if needed. We also have some more in-depth tips for safe biking in the pandemic, check them out! Please be aware that NOLA to Angola cannot provide logistical or emergency support to individual riders this year. Take care, and safe riding!